Tracking the Spring Bird Migration

Every spring and fall, the night sky comes alive with the sound of migration as songbirds join geese, ducks, herons, gulls, shorebirds, and more in an epic exodus that is one of the great natural wonders of the world. For the last several years, Harris Center Land Program Manager and bird migration enthusiast Eric Masterson has been operating a nocturnal flight call station in Hancock, recording and analyzing the calls of migrating birds as they pass unseen overhead. Learn more about this fascinating and little-known window into bird migration by following Eric’s field reports here!

Field Reports on This Page

April Sparrows Bring May Warblers

Solitary Sandpiper. (photo © Jen Goellnitz)

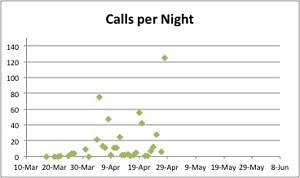

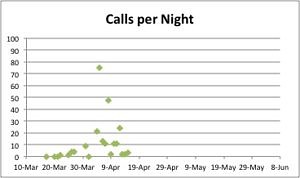

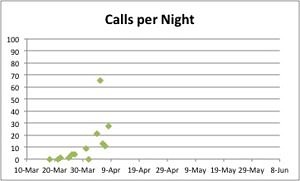

As the numbers build toward peak spring migration, there has been a noticeable shift toward warblers, as expected at this time of year. I am behind in processing the files because of the increased volume (I had to recalibrate the y-axis on May 2), so please check back in. Of note from the two nights linked below was a flight of White-crowned Sparrows on May 1 and a Solitary Sandpiper on May 2.

The conditions on Thursday night look excellent for migration, especially given the recent run of cold northerly wind.

Biggest Flight Of The Spring

Swamp Sparrow. (photo © Dave Inman)

April 28 saw the biggest migration event of the spring to date, with 125 calls from at least 11 species recorded from dusk to dawn. Fittingly for April, it was dominated by sparrows, with five species identified, including a good flight of Swamp Sparrows.

Expected time of arrival can greatly aid in the identification of species. The flight call of Swamp Sparrow is extremely similar to Lincoln’s Sparrow, but it’s about a week too early for the latter. Also, a Swamp Sparrow obligingly sang its distinctive song in the middle of the night, confirming that the species was on the move. Listen to the call here and see if you can tell it apart from the other sparrow species listed. It tends to be a bit buzzier. Three more Virginia Rails pushes the season total to 13 so far this spring.

Long-tailed Duck Flight

Long-tailed Duck. (photo © Fyn Kynd)

A pretty cool flight of Long-tailed Ducks passed over the house during the night of April 25. This handsome species is a high arctic breeder that winters off the coast of New England. It’s a stretch to call it a bird of the Monadnock Region; they use our airspace only briefly in spring, when at least some birds take an overland route north. They occasionally put down on inland water bodies when encountering bad weather, though they rarely stay long. Between 8:30 and 11:30 p.m., I recorded four separate migration events, indicating perhaps a broad-scale movement of the species. Click here for the audio – the birds were quite high as the signal is faint, but their call is very distinctive and they are an easy identification. Click here for a better recording I got on April 27, 2016.

Blue-headed Vireo – Yes And No

Blue-headed Vireo. (photo © Aaron Maizlish)

A wave of Blue-headed Vireos arrived in the region overnight on Saturday, April 24. A bird was singing from a nearby stand of hemlocks while I worked in the yard. Meade Cadot also reported his first of the season on the same day, as did several other birders throughout the region. I haven’t checked the audio files yet, but I already know that I won’t find a single recording of a Blue-headed Vireo.

Unlike most nocturnal migrants, vireos are silent at night. Assuming that wild birds don’t waste energy unnecessarily, it seems reasonable to assume that nocturnal flight calls serve a purpose. Why then would this practice not be universally applied across otherwise similar species?

For guidance, I went to the scientific literature:

Previous workers have suggested the birds give flight calls in response to fear, loneliness, hunger, or the approaching light of dawn. In some species, flight calls may signify the presence of a transient individual in a resident’s territory.… Other anecdotes suggest that some wood-warblers use flight calls in aggressive interactions….

However, I found the following statement to be the most compelling:

The consensus from the recent literature, together with anecdotal evidence, suggests that flight calls help to maintain groups, and stimulate migratory restlessness or ‘zugunruhe’ in conspecifics, perhaps especially in inexperienced birds … (Farnsworth, 2005).

I like the idea that nocturnal flight calls allow an individual bird to capitalize on the concept of group wisdom. This could be especially valuable to an inexperienced migrant, and Farnsworth cites evidence to suggest that young birds vocalize more frequently than adults. Call notes could foster group cohesion and help keep birds on the correct course heading, especially during periods of reduced visibility.

But the silent travelers still find their way to New Hampshire just fine. We really don’t know for sure why some birds call during nocturnal migration, while others do not. My bet is that there is indeed a social component to the calls, but that doesn’t explain why the Blue-headed Vireo that sang from my hemlock stand on Saturday couldn’t find its voice on Friday night. And I am okay with not knowing. We can put aside our insatiable quest for knowledge and simply savor the wonder of the moment. I don’t have to know why a bird sings to appreciate the song. To be honest, I am glad that there is still mystery left in this wonderful world of migration.

With thanks to Joe Gyekis.

Farnsworth, A., The Auk, Vol. 122, No. 3 (Jul. 2005), pp. 733-746

Pre-dawn Thrush Flight

Hermit Thrush. (photo © Jacob McGinnis)

With 46 nocturnal flight calls (nfc) detected, April 20 was another decent night for migration, though slightly down on the previous night. This is a common occurrence. The big rush usually happens at the first available weather opportunity. The backlog of migrants becomes increasingly depleted with each successive migration night, until bad weather causes another backlog to build and the process starts over.

Click here for the tally. Four individual Virginia Rails was noteworthy. Normally I avoid conjecture and confine myself to counting call notes, but based on the fact that four discrete recordings of Virginia Rail were recorded at distinctly different times, I feel confident that four birds were involved. There was also a decent pre-dawn flight of Hermit Thrush, with 25 nfc’s detected.

For those who wish to simply hear and appreciate nocturnal migration without delving into the nuances of identification, pre-dawn thrush flights offer the best opportunity for a variety of reasons. Compared to other species, thrushes are extremely vocal, especially just before dawn. Their call notes are fairly loud compared to warblers and sparrows, and they call in the lower frequency bands, meaning that the sound carries farther. My microphone can pick up thrushes flying more than 1000 feet overhead, whereas warblers and sparrows are undetectable at this range. And six species migrate through New Hampshire, most of which are fairly common. The downside is that you have to get out of bed an hour before sunrise. If you are not a morning person, maximize your chances by waiting for peak migration, which should hit sometime in the second week of May. Keep an eye on birdcast.info for updates.

Migration And Weather

Palm Warbler. (photo © Putneypics)

The seven nights of nocturnal migration ending Sunday tell a tale as much about weather as birds. With little migration for six days, followed by a ten-fold increase on Sunday night, I can surmise that a) the weather during the week up to and including Saturday was inclement to some degree, involving wind with a northerly aspect and/or rain, b) that this weather was regional in scope and not just confined to northern New England, and c) that there was a significant change in conditions on Sunday night.

The actual weather for the week was dominated by low pressure and wind, mostly westerly to northerly, which brought a procession of cold fronts across the region. There wasn’t much precipitation, but it didn’t matter. Most New England bound migrants prefer calm conditions in which to move, typically during periods of high pressure that bring weak southwesterly airflow and clear skies. And because birds that fly over New Hampshire may have started out in Connecticut the same night, the conditions that promote migration need to be regional in scope. Any bird wanting to move north needs to wait for a calm interlude. This came on Sunday night.

It didn’t last long though, with migration shut down again by Tuesday. Stationary high-pressure systems tend to dominate our landscape in summer, bringing extended periods of calm and clear weather. But these conditions are generally less common and shorter-lived in spring. This is why migration at this time of year is typically stop/start, with periods of heavy movement interspersed with periods when migration slows down or stops altogether. The longer the bad weather persists, the bigger the flight when it eventually passes. Think of that hated intersection where the light stays red forever. Lots of traffic moves when it finally turns green. On the other hand, stable high-pressure systems tend to persist into the fall. Consequently, bird movement is more smoothly distributed at this time of year.

Nocturnal Migration Over My Yard the Week of April 13

April 13: 2 migrants

April 14: 2 migrants

April 15: 3 migrants

April 16: 1 migrant

April 17: 2 migrants

April 18: 5 migrants

April 19: 56 migrants, including Virginia Rail, American Bittern, Chipping Sparrow, White-throated Sparrow, and first-of-season Palm Warbler.

A Mid-April Recap

It’s been very quiet since April 13 with a total of 7 migrants over the three nights; essentially zero migration. As soon as the weather turns more favorable (think high pressure), the pace will pick up. This is a good time to do the numbers.

Cumulative Numbers to Date

- Effort: 22 nights, totaling 202 hours and 15 minutes

- Species: 15 species detected migrating at night, including Wood Duck, Virginia Rail, Killdeer, Ring-billed Gull, American Bittern, Great Blue Heron, Hermit Thrush, American Robin, Chipping Sparrow, Field Sparrow, Dark-eyed Junco, White-throated Sparrow, Song Sparrow, Rusty Blackbird, Louisiana Waterthrush

- Call Notes: 241 call notes across 17 nights. Four nights with no migration. Nine nights with no recording due to inclement weather.

Virginia Rail And American Bittern

Virginia Rail. (photo © Tom Murray)

A couple of interesting visitors passed overhead during the night of April 12. Neither Virginia Rail nor American Bittern are commonly recorded as nocturnal migrants over my yard, though I usually have a few each season. Both are fairly secretive species, preferring to remain undetected in deep cover, and both migrate at night, so it is difficult to actually see either. But if you can catch a glimpse, they are magnificent looking creatures. Click here for the recordings, which also included Field and Chipping Sparrows.

Total migrant call notes: 25

Nightsongs Or Nightcalls?

Hermit Thrush. (photo © Becky Matsubara)

There was a decent flight of Hermit Thrushes over my yard on April 7 (10 birds) and April 8 (26 birds). There is nothing unusual in this. Hermit Thrush is the hardiest of the Catharus thrushes (Hermit Thrush, Swainson’s Thrush, Bicknell’s Thrush, Gray-cheeked Thrush, Veery) and the only one to overwinter in North America, with a few even braving out the New Hampshire cold every year. Unsurprisingly, they are the first back in spring, with big flights expected in mid-April.

Thrushes are very vocal migrants, calling abundantly especially during the pre-dawn. Click here to hear the nocturnal call note of a Hermit Thrush recorded from my yard on April 14, 2018. Much less is known about the concept of birds singing while migrating. I have recorded bird song at night several times, authored by multiple species. However it seems difficult to the point of impossible to definitively tie an instance of nocturnal bird song to an actively migrating bird. We have several species of birds in New Hampshire that commonly sing at night, including Northern Mockingbird, Ovenbird, and White-throated Sparrow. It seems that you would need something extraordinary to make a case.

I recorded something extraordinary at 0045 hours on April 8. Click here and listen closely to the unedited sequence and you will hear a Hermit Thrush singing several iterations of song, with each one louder than the last. I can make a very strong case that this bird is singing while in mid flight. As I write this blog post on April 13, my yard is still without a summer resident Hermit Thrush and so I am left to surmise that this bird was a migrant, winging its way north while in full song.

I reached out to Bill Evans, who coauthored Flight Calls of Migratory Birds with Michael O’Brien. Bill responded that he had never heard Hermit Thrush singing during migration and was of the opinion that song from night-migrating thrushes is rare. I can live with that. I have experienced rare before.

First Warbler Of The Spring

Louisiana Waterthrush. (photo © Bill Majoros)

There were considerably fewer migrants on the night of April 6 than during the previous night, but one of them was a bit special. Click here for the recording.

Louisiana Waterthrush is one of the less common of the 26 species of warblers that breed in New Hampshire. Difficult to separate from the more common Northern Waterthrush, Louisiana Waterthrush is noted for its habitat specificity. They are usually found alongside fast-moving streams. Fortunately we have lots of these in the Monadnock Region, and they’re great places to find this small warbler. A pair often breeds near the wooden bridge that spans Nubanusit Brook in Harrisville, accessible from the Eastview Trail. Listen and look for them with tail bobbing, perched on rocks or overhanging branches bordering the river.

What’s this I hear you say? If they’re hard to identify during the light of day, how can you possibly identify this bird at night, sight unseen, with just 80 milliseconds of barely audible noise as a guide? It’s a fair question, and one I would ask in your shoes.

Firstly, eliminate the alternatives. Louisiana Waterthrush is noted for the unusual timing of its migration. Arriving in the state by mid-April, the species is on territory fully a month before many other warblers have reached New Hampshire. On the back end, it is one of the first to leave, departing fully a month before many other species. They are almost unknown in September, when most other warbler species are still relatively common. In April, I don’t have to consider multiple alternative options. There are relatively few species in the state to cause confusion, and the ones that are here are separable.

Secondly, call notes, even very similar ones, can be distinguished with training. Just like birds have visual field marks – Louisiana Waterthrush is separated from Northern Waterthrush by a more distinct supercilium (line above the eye) and pinker legs – so their call notes sometimes have distinguishing markings when projected as a spectrogram. The CD-Rom, Flight Calls of Migratory Birds, Evans W. R. and O’Brien, M. 2002, describes the nocturnal call notes of many North American migrants. In addition to providing audio files, Evans and O’Brien describe each call in detail, with the following entry for Louisiana Waterthrush:

Measured calls (N=5) were 51.9-74.8 (76.7) mS in duration and in the 6.8-8.7 (7-8.4) kHz frequency range. The frequency track was single or double-banded and is level or slightly rising. It was evenly modulated with 3.5-6 (4.5) humps with a spacing of 13.6-17 (15.6) mS and a depth of 0.8-1.2 (1) kHz.

In other words, the call note looks like this , which is the recording I obtained on April 6. Other warblers that one might expect at this early date (Yellow-rumped and Palm Warbler) have a spectrogram that is quite different; sparrows and thrushes even more so. With time and patience, your ear can even start to distinguish the subtle differences previously discernible only to the eye.

, which is the recording I obtained on April 6. Other warblers that one might expect at this early date (Yellow-rumped and Palm Warbler) have a spectrogram that is quite different; sparrows and thrushes even more so. With time and patience, your ear can even start to distinguish the subtle differences previously discernible only to the eye.

Lastly, it is important to note that I might be wrong. Identification of nocturnal migrants by call note comes with a degree less conviction than does identification of birds by sight during the day. Still, I have a high degree of confidence that this 80 milliseconds came from a Louisiana Waterthrush winging its way north over my house on the night of April 6. I’ll still have to head out to the Eastview Trail in Harrisville this spring to put a face to the name.

Field Sparrow. (photo © Tom Murray)

Biggest Night Of The Spring, So Far

The night of April 5/6 marked the biggest flight of the spring to date, with 75 migrants, including more than 60 Song/Fox Sparrows (I don’t feel comfortable separating the nocturnal flight calls of these two) and the first Field Sparrow of the season. Click here for the eBird report, which includes recordings.

A Busy Week

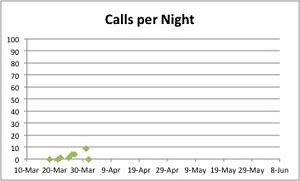

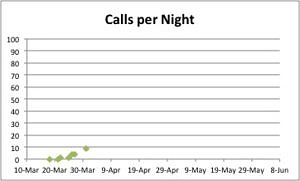

As you can see from the graph, the number of migrants is really starting to pick up. The weather this week was not as inclement as I expected, and consequently birds moved in decent numbers, especially last Sunday night. I have four days of reports to upload, which include some pretty cool recordings. More to follow.

Owl By Day, Goldfinch By Night

American Goldfinch. (photo © Colin Durfee)

Barred Owls are breeding nearby. They have been calling lately, both by day and by night, their vocalizations stealing time normally reserved for cardinals, goldfinches, and chickadees. This is not unusual in spring and early summer. The cover of darkness recedes when they are at their busiest, with hungry nestlings forcing them to work overtime. But I have never heard goldfinches calling from the owl’s domain, until tonight.

The mic picked up the unmistakable call notes of American Goldfinch at 9:30 p.m. on Saturday night, more than 2 hours past sunset. Click here for the night’s recordings. You can actually hear the Barred Owls hooting in the background. American Goldfinch range from the southern tip of James Bay in Canada all the way to Florida and the Gulf Coast. Some of the most northerly birds retreat south in winter, while some of the most southerly birds move in the opposite direction in summer. More than 2,500 have been counted migrating south along New Hampshire’s coast in a single day during the fall, and like phoebes, they are not known to migrate at night. I suspect this individual was disturbed from its roost, possibly by the Barred Owls.

Otherwise it was a surprisingly active night, considering the date and the weather forecast. In addition to goldfinch, 21 migrants passed overhead, including Killdeer, Ring-billed Gull, Great Blue Heron, American Robin, Dark-eyed Junco, and Song Sparrow. I should note at this juncture that the eBird protocol for recording nocturnal migration demands that calls are counted rather than individual birds, as it is impossible to know whether a call sequence represents one or multiple individuals. For example, my total of four Great Blue Herons actually represents two different audio events separated by hours, each event consisting of two calls. I think there were only two birds, but I can only state for certainty that there were four calls.

Silent Night

Ten hours of total silence. Not even a Barred Owl to mark the night. I was not surprised. The wind was 10 mph out of the north.

Migrants avoid wasting energy by unnecessarily fighting headwinds, preferring to wait out storms for fairer passage. And it is still early in the season. If it were May with similar winds, there would have been a few migrants.

The three main variables that affect migration are location, time of year, and weather. Location is a constant. Time of year is predictable. Numbers will start to spike later in April and through May. Weather is the great variable. Birds are hostage to its caprice.

The picture for the coming ten days is not favorable, with low pressure systems bringing adverse winds and rain across the region. There might be a few windows in which birds will be able to steal 50 or so miles. Sunday night is a possibility, but nothing worth waiting up for. If you’re interested in looking at the forecast as it pertains to bird migration, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology runs a terrific service called birdcast. It offers a three-day forecast of bird movement across the country by modeling weather, time of year, and other variables that determine large-scale bird movements. In the meantime, I will be back with reports as the weather breaks.

Cumulative Numbers to Date

- Effort: 87 hours and 20 minutes

- Species: Wood Duck, Killdeer, Ring-billed Gull, Chipping Sparrow, Song Sparrow

- Call Notes: 19

Killdeer And A Chipping Sparrow

Killdeer. (photo © Becky Matsubara)

Somewhere in the region of 30 shorebird species are recorded in New Hampshire every year, with most destined for breeding grounds far to our north. Killdeer and American Woodcock are two exceptions. To the best of my knowledge, the nearest Killdeer nest is at least a couple of miles away from my house. I live in the forest and they need bare open ground on which to lay eggs. The bird that passed overhead at 8:45 p.m. last night was likely a migrant. By contrast, another shorebird species, the wonderful American Woodcock, nests in my neighborhood. The bird that “sang” into the microphone at dawn on March 18 was likely recently arrived and on territory. It is worth a listen here.

Fellow travelers last night included several more Ring-billed Gulls and the first Chipping Sparrow of the season. Click here for audio.

Pop Quiz: what do Woodpeckers, Ruffed Grouse, and American Woodcock have in common? Hint: this is a blog about bird vocalizations.

A Happy Graph For A Change

Through the end of May I will be graphing the progress of bird migration as measured by call notes per night over my house. We are in the early stages now and the numbers will really start to take off toward late April, with hundreds of calls per night on peak nights. I don’t wish to make light of the pandemic, but I do wish to take our minds off it. Think less virus and more vireos.

Eastern Phoebes Reappear

Eastern Phoebe. (photo © Doug Greenberg)

The clear warm weather of late March facilitated the timely arrival of Eastern Phoebes across southern New Hampshire. I read a post online that hypothesized a large flight of phoebes during the night of March 27 on the evidence of multiple reports of birds seen across the state on March 28.

However, it is far from clear that Eastern Phoebes are a nocturnal migrant. Some of their close relatives in the flycatcher family travel by day, not by night. Massive migrations of Scissor-tailed Flycatchers have been observed during daylight hours from hawk watch sites in Mexico. Eastern Kingbird, another fairly close relative, is also a diurnal migrant. Perhaps most compelling is the lack of phoebe mortality relative to other migrants as a result of collision with e.g. television towers during the night.

I cannot leave you with a nocturnal recording of a migrant phoebe over my house from this spring. In fact, I have yet to knowingly record a single phoebe at night in five years and many hundreds of hours of recording nocturnal migrants.

Nocturnal Waterfowl

Wood Duck in flight. (photo © Stan Lupo)

I suspect most people think of songbirds when discussing the topic of bird vocalizations. But you might be surprised to learn that the majority of birds in North America can be distinguished by voice, including many species of waterfowl. I have recorded Brant (a goose that breeds in the high Arctic) and Long-tailed Duck (also a high Arctic breeder) migrating over my house, in addition to more expected species. Waterfowl start moving north early in the season, and by the end of March, their migration is largely over. My microphone caught this Wood Duck flying overhead at 4:30 a.m. on March 28. Their call is a very distinctive rising whistle. It is not too late to put up a Wood Duck nest box if you live near suitable habitat (a swamp or marsh). You can view design plans here.

Swallows (and Seagulls) are Back

Ring-billed Gull (photo © John Sutton)

Swallows are the poster child for bird migration, gulls not so much. Yet only one of these two left a voicemail on my recorder the other night. Hint: it wasn’t a swallow.

Swallows, immortalized in the legend of the Cliff Swallows of Mission San Juan Capistrano, returned to Hancock on March 26. Susie Spikol and I spotted a couple of Tree Swallows while cleaning out bluebird houses adjacent to Norway Pond. I didn’t record any on my microphone because swallows are diurnal migrants. (In other words, they don’t move at night, when my microphone is set up.) As a matter of fact, I can always tell when dawn has broken on the recordings, as that is when newly arrived Tree Swallows start chattering. They are usually the first birds up in the morning.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, gulls are perhaps the last birds to conjure up thoughts of migration. However, of the eighteen species that have been recorded in New Hampshire, most are migrants, at least to some extent. Ring-billed Gull, the most common species found along our coastline, is less common away from the coast but still the most likely gull species to occur inland, especially during spring and fall. They can be seen migrating north during the day along major river valleys, and I know that they also move at night. I recorded two birds moving north over my house on March 26, one at 10:30 p.m. and another at midnight. Click here to listen. (Turn your volume up.) They were likely headed to colonies in Vermont, Maine, or Canada. There are no known breeding locations in New Hampshire.

Total recording time last night: 9 hours. Total number of migrant call notes: 4.

A sole Song Sparrow — or possibly a Fox Sparrow — migrated overhead on March 25. (photo © Becky Matsubara)

The First Stirrings

I have recorded a total of 40 hours across four nights, with just one solitary sparrow passing north in that time. Likely a Song Sparrow, their nocturnal call note is extremely similar to the less common Fox Sparrow, so this species cannot be ruled out. Hear and see the call note here. The visual representation of the sound is diagnostic for many species that might otherwise sound similar.

One sparrow might seem underwhelming, but migration is a bell curve, and the season has barely begun. The abundance of May will be all the more impressive because we started listening during the Spartan weeks of late March. As we go through the season, I hope you will notice a correlation between what I record at night, and what shows up in your yard the next morning.

In addition to this one sparrow, my microphone has picked up the wing whistles of overflying waterfowl, which are early migrants, moving north through the state in March. Some birds are actually identifiable by their wing whistles. I suspect this bird is a Hooded Merganser.